The History of Mole, Mexico’s National Tesoro

- July 2021

- By Emilly Olivares

- Recipe from Mexico

The history of mole, the undeniable front runner for Mexico’s national dish, goes deep. Ask any Mexican, mole is our culinary treasure, a pure manifestation of our gastronomy at its most authentic and bedrock. The stew is rich in ingredients—most include dozens of chiles, seeds, nuts, spices—and a cornerstone of our national identity. Whether it’s homemade or store-bought, every bite of mole invites us to experience pre-Hispanic cultura y comida—and at the same time, acknowledge the centuries of hardship, ambition, tradition and innovation that make it possible for us to be able to order mole pretty much any day we want it in the U.S. and Mexico today.

How did we get here? Let’s take a mole trip back in time.

The First Mole in the History Books

The earliest known reference to mole in historical records dates to a 16th-century review of mesoamerican ethnography: Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España written by friar Bernardino de Sahagún. In his account, we come to learn about Los Aztecas’ elaborate ritual preparations to honor Xiuhtecuhtli, the Aztec God of Fire.

De Sahagún wrote that in addition to tamales, he saw served a type of crawfish called “acocil” with a stew they called “chalmulmulli.” We draw your attention to the last third of this word: mulli—or as it’s also spelled: mōlli. In classical Nahuatl, an uto-Aztecan language, mōlli means “sauce” or “mixture,” giving us our current mole. The Aztec sauciers cooked and mashed together pre-Hispanic ingredients such as pepitas (pumpkin seeds), xocolatl (Nahuatl for “chocolate”), tomatoes, and chiles (from the Nahuatl chīlli, for “hot pepper”).

They mixed them together in molcajetes made of stone to achieve a creamy delicacy. Guacamole, or as the Aztec people called guac in Nahuatl: āhuacamōlli, shares the same goal (mashing) and etymological root (mōlli), though they were only mixing together one ingredient: āhuacatl: yep—avocado, instead of chiles and spices.

Whether it’s homemade or store-bought, every bite of mole invites us to experience pre-Hispanic cultura y comida.

History of Mole Fact Check: Did Nuns Really Invent the Dish for a Bishop?

Over time, as some of the indigenous women found work in convents and churches, their pre-Hispanic recipes were passed on and served outside of their tribes. Inevitably, new ingredients came by ship from Spain and other lands across the oceans—like nuts, cinnamon, anise, ginger and black pepper. These were introduced into an ever-expanding mōlli for the evolving mesoamerican palate and Mexico’s recipes.

Along the way, apocryphal myths about the origin of mole sprang up and have lasted for hundreds of years, despite their lack of historical fact.

In the history of mole, one of the most popular, enduring—and likely untrue—tales is the one about the nuns and the bishop. Allegedly, in 1885, the tale goes (with zero definitive historical record), the convent of Santa Rosa got word that the bishop of Puebla Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz was on his way for a special visit—and surely expecting an excellent dinner. One nun, sor Andrea de la Asunción, scrambled to prepare a dish worthy of this dignitary. According to lore, she and the nuns threw together more than 100 ingredients into a new, extraordinary sauce. They grabbed a local turkey, cooked it, smothered its tender meat with their just-invented salsa—and rocked the bishop’s and the food world’s taste buds forever.

Another version has the visit being from the 17th-century viceroy of New Spain, Tomás de la Cerda y Aragón, the third marquess of la Laguna. But no matter who was coming to dinner or how charming the tale may be, there is likely not a shred of truth to it.

That there are so many stories explaining the origins of mole underscores how important the dish is to our Mexican identity. It transports us through time back to the Aztecs, to the Spanish conquest, to the mix of Spanish and indigenous traditions, and even to the later influences of Asian and Middle Eastern immigration, imparting new touches to our native dish.

When Is Mole on the Menu in Mexico?

Some 400 years ago, mole was a time-consuming dish prepared on special occasions—and not much has changed! The process of making mole from scratch is laborious—and therefore a show of respect for those coming over, be they family, friends or national dignitaries.

Depending on the type of mole you’re making, you may find yourself using up to 50 ingredients—which is the point. Mole is muy especial and honors those who share the meal. Today, mole continues to be served at our most important occasions that require commemoration: baptisms, birthdays, quinceañeras, weddings, anniversaries, national feasts like Mexican Independence Day on Sept. 16, the Day of the Dead, and funerals. Cradle to grave.

7? 20? 50? How Many Moles Are There Really?

More than 50 variations of mole are said to exist, although there is no definitive culinary or official record. Lore also has it that each town in Mexico has its own traditional mole recipe—although again, there is no definitive source giving proof to each pueblo’s unique receta.

That said, most history of mole roads seem to lead to two cities of origin: Puebla, credited as the birthplace of the dish, and Oaxaca, renowned for its seven moles. Can you name all siete?: amarillo, chichilo, coloradito, manchamantel (tablecloth-stainer), rojo, negro, and verde.

Did you know that there is even a mole blanco? Its pale color comes from its ingredients: peeled almonds, peanuts, white chocolate—but don’t let the almond-vanilla hue fool you. There can’t be mole without chiles!

What Ingredients Are in Moles?

What makes moles different from each other is their unique combo of chiles, nuts, spices, vegetables, fruits and meats. As we break down the ingredients of your moles favoritos, how each gets its name, color and recommended food pairings starts to become clear.

Here is a quick primer of the most familiar moles of Mexico:

Mole Amarillo

Chiles:

Chilcostles or chilhuacles amarillos, guajillos, anchos, costeño amarillos

Also includes:

Chayote, zucchini, green beans, potatoes, and spices

Serve with:

Chicken or turkey, with a side of white or Mexican rice

From:

Oaxaca

Mole Chichilo

Chiles:

Chilhuacle, ancho

Also includes:

Chayote, green beans, green tomato, avocado leaves, onion, garlic, tomato and spices

Serve with:

Chicken or turkey, with a side of white or Mexican rice, garnish with sesame seeds and slices of onion

From:

Oaxaca

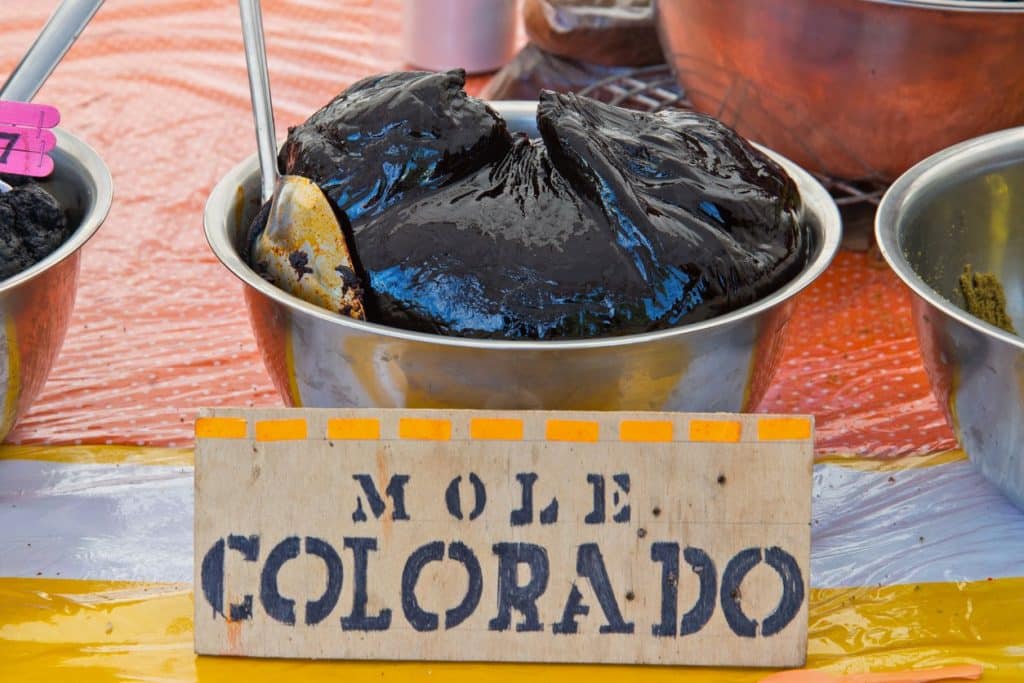

Mole Coloradito

Chiles:

Ancho, chilcostle, guajillo

Also includes:

Chocolate, plantain, cinnamon, tomato, garlic, sesame seeds, and other spices

Served with:

Chicken or pork, with a side of white rice.

From:

Oaxaca

Mole Manchamantel

Chile:

Anchos

Also includes:

Apple cider vinegar, peanuts, raisins, bread, cloves, cinnamon, and other herbs and spices

Served with:

White rice and vegetables

From:

Oaxaca, Puebla

Mole Negro

Chiles:

Chihuacle, mulato, pasilla

Also includes:

Plantains, pumpkin seeds, peanuts, chocolate, almonds, raisins, sesame seeds, and various spices

Serve with:

Chicken or turkey, white or Mexican rice, garnish with sesame seeds or slices of onion|

From:

Oaxaca

Mole Poblano

Chiles:

Ancho, guajillo, pasilla

Also includes:

Cinnamon, almonds, pumpkin seeds, peanuts, chocolate, tomato, garlic spices, and herbs

Serve with:

Turkey or chicken, with a side of Mexican rice

From:

Puebla

Mole Rojo

Chiles:

Guajillo, ancho

Also includes:

Plantain, sesame seeds, peanuts, almonds, chocolate, raisins, herbs, and spices

Serve with:

Chicken, turkey, or pork, with a side of white or Mexican rice

From:

Oaxaca, Puebla

Mole Verde

Chile:

Serrano

Also includes:

Green tomato, green beans, epazote, chayote, garlic, and other spices

Serve with:

Chicken or turkey, with a side of white or Mexican rice

From:

Oaxaca

Did you notice not a single type of mole excludes pre-Hispanic ingredients? This is a testament to the mole’s centuries-long central role in Mexican culture, tradition and comida history.

Ready to Make Mole? Try These 3 Favorite Familia Kitchen Recipes

If the amount of ingredients to cook a mole overwhelms you, no te preucupes! Worry no more. The mole pastes at your local grocery store are usually top-notch and carefully blended with quality, authentic ingredients. Plus, you can always add your own chiles and other spices and local produce to make the mole you like best—like this family does with their chicken enchiladas with mole. At least two generations of women in Patricia Lopez-Piotrowski’s familia have been making this delicious mole dish for the men they love with pre-made sauces (with stellar romantic results: all three generations got engaged right after serving these enchiladas. True story. Read it here.).

If you want to try your hand at making mole for your next special occasion, check out these family-favorite recipes submitted by the Familia Kitchen community:

My Aunt Coty’s Mole with Guajillos, Cocoa and Peanuts (or Peanut Butter!)

Our Secret Family Mole Recipe From Abuelita Paz

Arcelia’s Family Mole de Jalisco

Mole making is a powerful ritual that blends ancient and modern culinary practices. And it’s still served at our most meaningful meals with familia and friends. It’s worth the work and time we put into it: A good mole is velvety, earthy, spicy, smokey, sometimes sweet—and always delicioso.

Connecting our Mexican past to our Mexican present, mole will carry us forward into the next generation’s food rituals and gatherings. Mole will continue to bring families and friends together, and welcome important guests to our country. Those of us living in the U.S. can cook our way home when we make mole for ourselves and others. It’s how we express ourselves as Mexicans, no matter how old we are, where we live now, or what language we speak at home and work.

Because mole is our Mexican love language.

MoreLike This

Got a question or suggestion?

Please rate this recipe and leave any tips, substitutions, or Qs you have!