Is Latino Cuisine Even a Thing? Hear Us Out: 3 Reasons Why

- September 2023

- By Kim Caviness

- Recipe from Everywhere Latino

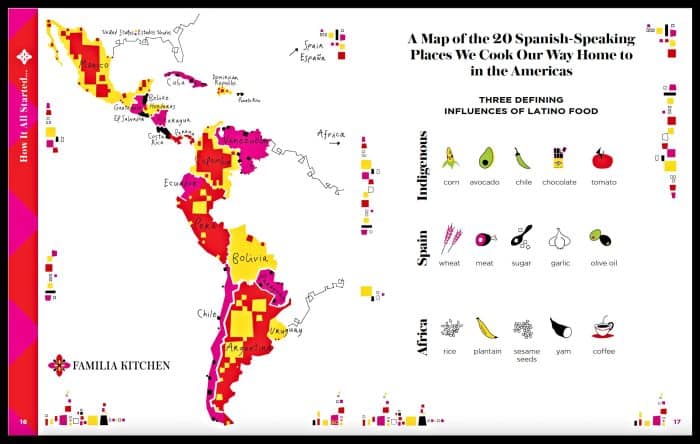

At Familia Kitchen, we gather and celebrate family-famous dishes that so often live only in homecooks’ minds and memories. We preserve them on our website, in our cookbook and newsletters to help pass them on to the next generación: our children and their children. But if Latinos come from 20 wildly different homelands (from the Andes mountains of Perú to the deserts of Mexico to tropical Puerto Rico) and use ingredients and techniques that result in dishes as disparate as Mexican tacos de papa and Cuban ropa vieja — the question must be asked: Is there even such a thing as Latino cuisine?

Just because we come from places that happen to speak español and lots of us love avocados, is that enough to connect our dishes into one common cuisine?

—A question we think about a lot at Familia Kitchen

Just because we come from places that happen to speak español and lots of us love avocados, is that enough to connect our dishes into one common cuisine?

We’ve thought about this question a lot.

And we have come down on the side of: yes.

Sí, there is such a thing as Latino cuisine. And it goes way beyond avocados. Here are three commonalities that bind its 20 very different destinations’ approach to food and culinary heritage into one glorious cuisine.

1. Latino Cuisine Emerged From Spanish Colonialization

Throughout the 1500s and 1600s, all 20 Spanish-speaking Latino nations and islands were colonized by waves of Spanish conquistadores. Aboard their ships, along with land-grabbing intentions, came Spanish ideas of how and what to eat. Los españoles brought olive oil, livestock, chickens, pork, wheat and the technique of sofrito, a cooking base of sautéed garlic and onion. The plan? Impose their culture, including their cuisine, on the Indigenous locals: Aztecs, Mayas, Incas, Arawaks and other Native communities. But comida change doesn’t just happen one way. Spanish tables were turned and soon stocked with indigenous ingredients like corn, avocados, tomatoes and chiles. These were later joined by African staples. When the Spaniards needed forced labor, they cruelly turned to enslaved people from western Africa, who brought rice, plantains, yams, sesame seeds, coffee and more.

To see how colonialization melded these influences into a new cuisine, consider the taco. It’s made with masa harina and chiles (Indigenous), filled with meat and garlic (Spanish), and often served with a side of rice (African) and beans (Indigenous).

2. Latino Cuisine Honors “Poor People” Food

Latino food is humble food. It often stars discarded animal parts and ingredients salvaged from the trash bins of early Spanish kitchens. Indigenous and African communities learned to master cooking with meat scraps and fruit, roots and vegetables they could affordably grow. Think: beef organs, pigs’ feet, yuca, taro and plantains. These so-called “poor people” ingredients became the bedrock of the cuisine that emerged. Which is why today we still feast on centuries-old dishes like sancocho in the Dominican Republic; pozole in Mexico; arroz con gandules in Puerto Rico; and offal at an Argentinian asado. This earthy fare is so prized it’s now reserved for holidays and special family events. Take sancocho, traditionally made for fiestas in the D.R. This stew is made with plantains, yuca, taro and cheap cuts of pork, beef and/or chicken. In the pots of enslaved African and Indigenous cooks, humble dishes like sancocho transformed into national treasures that endure.

3. Latino Cuisine Is an Abrazo of Bold Flavors

Think of the British meat pie: Cook beef. Mash potatoes. Mix and cover in dough. Bake. Done. Now think of the carne asada taco — essentially the same dish: cooked beef and dough. Except the Mexican favorite offers layers upon layers of flavor. First, the masa harina is shaped from nixtamalized corn into fresh tortillas. Then, the beef is marinated in chiles, garlic, onion, lime, cilantro and salt. More chiles are toasted to cook with the meat. Salsas are drizzled over the carne. And finally: Before it meets your mouth, the taco is topped with avocados, radishes, onion, cilantro and crema. That’s a whole lot of flavor layers! The point is to build—not blend. The spices and ingredients are designed to hit your mouth in waves. Because in comida latina, more is mejor and bold is better. Siempre.

At Familia Kitchen, dish by dish, we explore how these three comida commonalities play out across the family-famous authentic recipes from homelands to create one grand cuisine: Latino.

Bienvenidos y buen provecho, everyone. Welcome to our Familia Kitchen.

MoreLike This

Got a question or suggestion?

Please rate this recipe and leave any tips, substitutions, or Qs you have!