Venezuela’s Food History—Arepas, Hallacas y Más!

- November 2021

- By Emilly Olivares

- Recipe from Venezuela

At the heart of Venezuela’s food history and culture, arepas are an essential part of every meal. Unless of course, arepas are the main meal. To understand how this bread came to play such a central role in Venezuela’s cuisine, I dug into the history of Venezuela and the food stories shared by Venezuelan madres, abuelas and their abuelas.

Anthropological evidence suggests Venezuelans have been making and eating arepas for more than 2,000 years. Before Spanish colonization, the cornmeal patties were already traditional to the territory that is now Colombia and Venezuela. Maíz grew generously across the land and indigenous tribes learned to cultivate it. This led to what the Cumangoto tribe called erepa, their word for both the corn ingredient and the beloved pansito.

Through phonetic evolution and foreign influence, erepa became arepa and it has remained a daily source of sustenance through and beyond colonization to our current times. In the early days, before there were such things as stores and mercados, people had to hand make their own flour and then the dough. The process began by transforming whole maiz to harina; that is, turning corn into flour by cleaning, grinding, cooking, and milling it, a time-consuming sequence of steps that usually took more than a day. Once the masa was ready, areperas would shape a small chunk of dough into a thick disc and place it on hot budares or griddles made of iron or clay until it cooked all the way through.

That’s a lot of work for a daily staple, right? A few things have changed since then!

Arepa lovers should all give thanks to Venezuelan engineer Luis Caballero Mejías. In 1954, Mejías initiated a process that ultimately resulted in the first patent for precooked corn meal. A few years later, a Venezuelan company called Empresas Polar introduced P.A.N, a precooked cornmeal product that revolutionized daily life in Venezuela. Suddenly the making of daily arepas went from a full-day chore into one that took just minutes. Homecooks across the nation surely cheered that day. P.A.N., by the way, stands for Productos Alimenticios Nacionales—National Nutritional Products.

How We Love Arepas—Let Us Count the Ways

Arepas are hot: hot as in calientitas and hot as in popular. They are eaten any time of day, as a snack, side or the main meal. They are served solo, stuffed or in soups like the delicious pisca andina, made with chicken broth, potatoes, cheese and milk. The range of arepa fillings in Venezuela’s food history is mouthwatering and we want to try them all.

Here are some of the most popular Venezuelan arepa rellenos:

- Reina Pepiada

Named after a Venezuelan beauty queen, this light chicken salad is made with diced onion, avocado and mayo and topped with fresh slices of aguacate. - Domino

It got its name because it resembles a black-and-white domino with its mix of seasoned caraotas negras (black beans) and shredded queso. - Pelúa

Pelúa means hairy, which is how this arepa looks thanks to the carne mechada (shredded beef) and shredded cheese filling strands poking out of the opening. - Perico

This arepa is a favorite for breakfast—it’s filled with eggs, tomato and onion. Its name means parrot, perhaps because of its bright colors?

Arepas are simple to make—learn how from one of Familia Kitchen’s favorite Venezuelan cooks Liliana Hernández. With practice you will be able to get them to just the right shape, texture and level of toasty golden-brown.

Join us as we raise our arepa to toast maíz. This simple ingredient nourished our Latin American indigenous ancestors who discovered, worshiped, and transformed corn into a food that continues to inspire innovative preparations and techniques across Latino countries and the world.

That said, corn is not the only native ingredient that defines Venezuelan cuisine. Let’s look at some of the others.

The Essentials Foods & Ingredients

Venezuelan regions range from the Andes to the coast, Amazon jungles and the plains. Depending on the area, the preparation and list of ingredients for the nation’s staple dishes vary. In the Andes, for example, the arepa is made using wheat flour.

Still there are a few essential ingredients and products that, regardless of location, are absolutely necessary in preserving the country’s traditional flavors.

In addition to corn, plantains, yuca, bananas and coconuts are native crops that grow in abundance and are important for the economy and the daily diet of Venezuela. Spanish colonization brought new ingredients that were quickly adapted into native cooking practices. Here is a roundup of defining elements of Venezuela’s food history and culinary landscape.

Seafood & Meat

The coastal regions and beaches of Venezuela offer fresh seafood, while in the Andes you find a selection of beef and lamb cured meats.

Cheese

Popular cheeses in Venezuela are soft queso blanco, mozzarella-like queso de mano and shredded hard-cheese queso rallado. Cheese is used as a topping with many traditional arepas.

Rice

White rice is an essential side to dishes like pabellón criollo (more on this plato, below). Rice is also necessary for the preparation of chicha, a cold and refreshing traditional drink made with arroz and vanilla.

Beans

Called caraotas negras, black beans are loved in Venezuela. They are eaten for breakfast, lunch and dinner and used in some arepas.

Beyond the Mighty Arepa: What Else Do Venezuelans Eat?

The National Dish of Venezuela: Pabellón Criollo

What it is: A traditional plate combining white rice, black beans or caraotas negras, tajadas (fried plantains), and shredded beef. A few basic ingredients—onions, garlic, bell peppers, cumin, and tomatoes—are absolutely necessary in the preparation of this platillo tropical clásico that ensures a colorful presentation and sabor auténtico!

This colorful dish is said to look like the former version of the Venezuelan flag, which was black, red and yellow.

Hail the Hallacas: the Venezuelan Holiday MVP

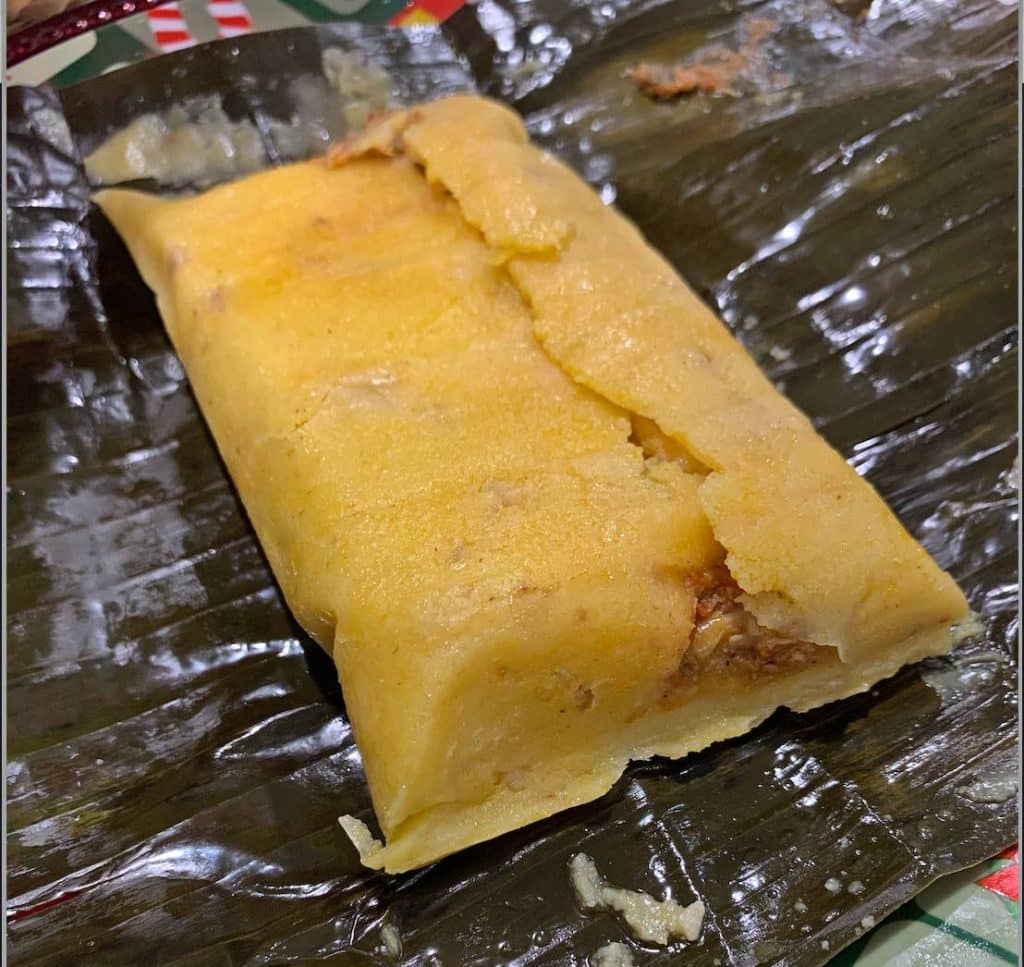

What it is: Venezuela’s take on the tamal and a vibrant expression of multicultural culinary fusion. Hallacas are traditionally made by a family assembly line for the Christmas holidays, with corn dough wrapped and steamed in plantain or banana leaves.

Depending on the region and recipe, they’re stuffed with a guisado or stew made with meat, pork or chicken. The traditional hallaca filling also includes a mix of olives, red and green bell peppers, onions, raisins, capers, hardboiled eggs, and nuts.

Each hallaca is then skillfully closed, tied and tightened with the help of more plantain leaves and cooking twine before being placed in a large steamer. When done, each bite of the hallaca’s tasty parcel delivers layers of flavor for the holiday family celebration.

The hallaca’s exact origin isn’t recorded, however lore and food historians suggest that the dish was created during the Spanish colonization period by enslaved indigenous and African people. On festive occasions, they were known to gather the leftovers from the kitchens of the wealthy Spanish. Using masa de maíz, which we know was abundant and easy to access, they would make masa, fill it with the remnant comida, and wrap the resulting rellenos in banana leaves, for steaming.

Making hallacas is definitely a team effort. It means all hands on deck, and better yet, all hands in la cocina. The process typically takes two days. Tradition reserves this food for special occasions like Christmas and New Year’s. What better time to give our madres and abuelas our helping hands and full hearts?

Y el Postre?

At Familia Kitchen, we believe that there’s always room for dessert. Anyone who says otherwise obviously hasn’t tasted cake. Speaking of cake, have you heard of the one called bienmesabe? This must-try dessert features layers of bizcocho drenched in a sweet milky syrup, coconut cream, and meringue. The melody of the name itself: bienmesabe—which means: ittastesgoodtome—promises sabor y felicidad.

Bienmesabe is a popular postre across Latin America with many recipe versions. It is of Spanish origin, specifically from the regions of Andalusía, the Canary Islands and Málaga. In Venezuela, the technique for making this time-consuming, much-loved sweet was introduced by the españoles. Over time the treat evolved to include the milk and pulp of fresh coconuts in the exalted version we worshipfully sink our forks into today.

A Vibrant Display of Venezulan Food History & Pride

I recently visited a local Venezuelan restaurant in Chicago and asked our waiter, who was born in Caracas, if she could describe Venezuelan comida using a single word.

She said, “espectacular,” and then corrected herself: “No, sabrosa!”

I couldn’t agree more. My journey into the history of its foods—first and foremost the mighty arepa, its culinary culture, and native ingredients made me realize the deep love that Venezuelans have for their traditional comida. I don’t think the bounty of the dishes and drinks on our table at the Chicago restaurant was much different from what hers looked like growing up in Venezuela. Arepas, pabellón criollo, caraotas negras, bienmesabe.

The table looked beautiful, filled with plates in a colorful spread of hearty and flavorful food, starting with the estrella of the Venezuelan daily diet: arepas!

And yes, our waiter was absolutely right. The arepa and everything on our plates was espectacular and sabrosa.

Hungry for Venezuelan food? Check out the recipes sent to Familia Kitchen by one of our favorite Venezuelan cooks, Liliana Hernández (you can also watch her make them step by step on her YouTube channel, Mi Show de Cocina). Don’t miss her melted-cheese tequeños, pabellón criollo, fall-apart-in-your-mouth asado negro beef, and life-changing bienmesabe coconut and meringue cake.

Photos: Michelle Ezratty Murphy and Liliana Hernández

MoreLike This

Got a question or suggestion?

Please rate this recipe and leave any tips, substitutions, or Qs you have!